Around 2012, the La Marzocco engineering department noticed something: the flowmeters that were used in automatic/volumetric espresso machines lost accuracy when the espresso flow rates slowed down. “In this case, the water bypassed the flowmeter, so the impeller was unable to count the number of revolutions,” says Riccardo Gatti, R&D Manager for La Marzocco. This was a problem because third-wave specialty coffee bars were starting to explore volumetrics to increase consistency during busy rushes, and these cafes often ground coffee finer and pulled slower espresso shots. To address the issue, however, it was important for the team to assess the current coffee landscape and look back to La Marzocco’s history of using volumetric flowmeters while imagining the future of espresso technology.

How Flowmeters Work

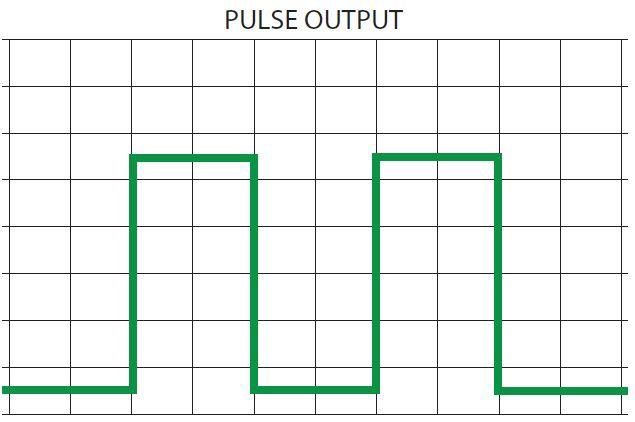

The volumetric flowmeter is used in a variety of applications, not just espresso machines. Flowmeters are often used to measure both the quantity and the flow rate of water or gas—they’re commonly used by water and power companies to calculate the utility usage of buildings. Inside the flowmeter is an impeller—a little disc with paddles that looks a bit like a windmill. One of the paddles on the impeller has a magnet on it, and every time it spins a full rotation and passes a sensor, it creates an electric signal known as a “pulse.” This way, the impeller can track the number of rotations, or “pulses,” which can then be registered as a unit of measure.

When installed in an espresso machine, flowmeters are used to track total water volume in the number of pulses tracked by the impeller. This means that when a barista sets the flowmeter to be programmed, it records the number of times the impeller spun and is able to repeat that same process. However, flowmeters rely on consistent flow rates of water in order to be accurate. An espresso machine pulling a shot of espresso, where the coffee creates resistance, is going to create a different reading than the water flowing through the espresso machine without coffee in the portafilter. This is why espresso machines are only accurate in recording the proper water volume when a barista is pulling a shot.

Volumetrics at La Marzocco

Flowmeters have been used in La Marzocco espresso machines since the early 1990s and were initially seen as a major upgrade from semi-automatic machines that required baristas to start and stop every espresso shot manually. But when third-wave coffee started approaching the sourcing, roasting, and brewing process with a larger emphasis on quality and specific flavor profiles, there was a shift back to semi-automatic espresso machines to emphasize the craft of making espresso. Modern cafes wanted to highlight that every coffee was made specifically for each customer to order, and moving away from volumetric espresso was one way to do so.

For most of the 2000s, third-wave specialty coffee bars focused on manually pulling shots of espresso, but La Marzorcco was still improving on volumetric technology. “With the GB5, we finally introduced the group cap solution where Piero Bambi integrated the volumetric counter into the group to reduce the thermal dissipation,” says Gatti. Older machines installed the flowmeter just outside of the group cap, which created a slight loss in temperature as water passed through it on the way to brew espresso. The Piero cap, as it became known, improved both the thermal stability of the water headed to the group cap and the accuracy of the amount of water dispensed since the flowmeter was now internal.

The Rise of Scales in Espresso

Around 2010, things began to change. Espresso techniques were often taught to newer baristas by filling the portafilter basket and leveling off excess coffee, pulling the shot to a volume marking, and tasting coffee to decide the quality. While this method taught baristas how to make espresso by using their senses, most baristas had their own techniques that made it hard to stay consistent throughout the day. In 2010, Vince Fedele introduced the use of a refractometer to measure coffee extraction. Now, baristas had a device that allowed them to see exactly how concentrated their espresso shots were, but the refractometer also had another impact on making coffee: to get an accurate reading, you had to input the weight of the coffee used as well as the weight of the espresso itself.

Now that baristas were weighing their input and output, creating a specific brew ratio, it became easier to track espresso quality and stay consistent. The appearance of scales used to make espresso showed that modern cafés were interested in accuracy and consistency, and the R&D team went to work. “We tested in the lab, and I remember personally how many coffees we did at the time. Tons of espresso shots were pulled trying to find the correct size of the gicleur that increased force that the water had on the impeller,” says Gatti. The flowmeter’s accuracy was improved by 2012, and shortly afterward, specialty coffee started to adopt the technology in their cafes.

Embracing Volumetric Espresso in Third-Wave Coffee

In March 2013, Ben Kaminsky wrote a guest blog for La Marzoco USA that examined the consistency of trained baristas vs. a volumetric espresso machine. He found that trained baristas were 50% more consistent and 50% faster using volumetric espresso machines than pulling shots by sight and time alone. These results, along with other tests by known baristas at the time, dramatically shifted third-wave attitudes towards automation in espresso. Part of the reason that the machine was so accurate is that volumetric flowmeters are designed to be very precise: each pulse recorded on the machine is only a fraction of a milliliter.

This laid the foundation for the launch of the Linea PB one month later, in April 2013. The Linea PB expanded on the improved flowmeter with both the Piero cap and an updated electronics system, which, for the first time, had a computer inside that used software to track and program the flowmeter. This allowed baristas to dial in their espresso more easily and even edit the volumetric shot that they had just saved by changing the number of pulses in the programming menu. “At the time, it was a mistake because we accidentally released lab firmware. We developed an internal firmware to check the number of pulses on the display, and this update was sent to the public by accident. But customers loved it, and so we released the update to every Linea PB,” says Gatti. With the ability to directly edit the number of pulses, baristas could now refine the volumes that they programmed instead of having to pull the espresso shot again to reprogram the machine.

The Advent of Drip-Tray Scales and the Swan Grinder

But the R&D team wasn’t quite finished with their pursuit of accuracy. At the same time that they were developing an updated flowmeter and the Linea PB, they were also developing the drip-tray scales that would be included in La Marzocco ABR espresso machines. When the Linea PB with scales was released in 2015, people were ready to adopt the new technology to bring even more accuracy and consistency to their espresso bars because they had already embraced volumetrics. And while the initial data using scales to predict espresso flow rates went on to lay the foundation for Stada X mass-based pressure profiles, there was another discovery that the team made at this time: the Swan’s grind-by-revolution programming.

“In terms of dose, so we applied the same technology that we had on the espresso machine to the burrs of a grinder,” says Gatti. With the improved accuracy of the updated flowmeter and software of the Linea PB, La Marzocco’s R&D team was able to reimagine the espresso grinder, developing technology that was never before used in grinding.